Expulsion of the Cherokees

|

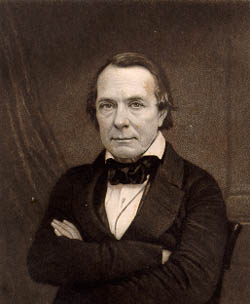

President Mirabeau B.

Lamar |

President Mirabeau B. Lamar, who took office at the end of

1838, had a very different attitude towards Indians than did

Sam Houston. Lamar believed that the Indians had no integrity;

thus, there was no possibility of peaceful negotiation or

co-existence. The only solution to the violent clashes between

whites and Indians was to rid Texas of the Indians--permanently.

Lamar spoke for the majority of white Texans, who had wearied

of Sam Houston's peace efforts. Houston had achieved little

cooperation with the Texas Congress, which ratified almost

none of his treaties. By contrast, Congress was quick to pass

Lamar's frontier defense bills and appropriated more than

a million dollars to pay for troops, military roads, and forts.

Relations with the Cherokees

were the first to come to a boil. Lamar hoped to convince

the Cherokees to leave Texas peacefully, but he made it clear

that if they did not leave, they would face unmerciful military

action. Lamar sent a commission of leading hard-liners, including

David G. Burnet, Thomas J. Rusk, and Albert Sidney Johnston,

to negotiate the removal of the tribe to the Arkansas territory.

He also deployed about 900 army regulars, volunteers, and

militia to East Texas.

Fearful of being attacked, the Cherokees retreated to a fortified

Delaware village near Camp Jackson. On July 15, 1839, several

hundred warriors under Chief Bowl engaged the Texans near

present-day Tyler. In the initial battle, the Indians were

defeated, losing eighteen men to the Texans' three. The next

day, the Texans pursued the retreating Indians and inflicted

more than 100 casualties, Chief Bowl among them. They also

burned the Indian villages and chased the Indians across the

Red River into neighboring Indian Territory (Oklahoma). In

the aftermath, many of the weaker or more peaceful tribes

in East Texas were also forced to relocate.

| |

Lamar

Declares, "No Compromise," 1838

Most Texans agreed with Lamar that Indians and whites

could not live together as neighbors. Lamar instituted

a hard-line policy that he hoped would result in the

expulsion or extermination of Indians from Texas.

House Journal, Third Congress of the

Republic of Texas.

|

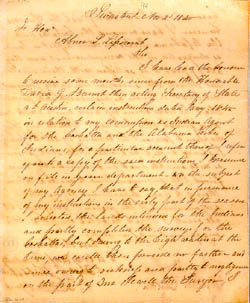

"The

Cherokee Can No Longer Remain Among Us"

In this letter to Shawnee

chief John Linney, Lamar denounces the Cherokee alliance

with the Mexicans and urges the Shawnees to remain

neutral in the event of war. The Shawnees kept the

peace but were eventually forced to leave Texas, though

they received some compensation for the crops and

property they were forced to leave behind.

Texas Indian Papers Volume 1, #35.

Mirabeau B. Lamar to John Linney, May 1839. |

|

| |

Lamar

Orders the Cherokee Removal, 1839

After discovering evidence of a Mexican plot to ally

with the Indians to overthrow the Republic of Texas,

Lamar abandoned any efforts to find a peaceful solution.

He sent troops to occupy the Neches Saline area and

notified Chief Bowl that his people would be removed

beyond the Red River, by force if necessary. The Cherokees

decided to fight.

Texas Indian Papers Volume 1, #36.

Mirabeau B. Lamar to David G. Burnet, Albert Sidney

Johnston, Thomas J. Rusk, I.W. Burton, and James S.

Mayfield; June 27, 1839. |

Kelsey Douglass to Secretary of War Albert Sidney

Johnston, 1839

In July 1839, Texas congressman Kelsey H. Douglass

was put in command of approximately 500 troops and

ordered to remove the Indians to Arkansas Territory.

On July 15, the final peace negotiations failed, and

Douglass marched on the Cherokee village.

Mirabeau B. Lamar Papers # 1373. Kelsey

Douglass to Albert Sidney Johnston, July 17, 1839.

|

|

|

|

Relocation

of the Alabamas and Coushattas, 1840

The defeat and expulsion of the Cherokees changed

life for many other tribes in Texas. By 1841, East

Texas was almost entirely cleared of Indians. The

Alabamas

and Coushattas were exceptions. A peaceful tribe

who had aided the Texans during the Runaway Scrape,

they were granted two leagues of land along the Trinity

River.

Texas Indian Papers Volume 1, #94.

Thomas G. Stubblefield to Secretary of State Abner

L. Lipscomb, November 2, 1840. |

In This Section:

Expulsion of the Cherokees -The

Comanche War -

Treaty Negotiations

- Trade

Next Section

- Table of Contents

- HOME

|